Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Korean J Community Nutr > Volume 30(5); 2025 > Article

-

Review

- Evaluation and standardized dietary strategies for dysphagia in older adults: a narrative review

-

Jean Kyung Paik†

-

Korean Journal of Community Nutrition 2025;30(5):323-330.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5720/kjcn.2025.00290

Published online: October 31, 2025

Professor, Department of Food and Nutrition, Eulji University, Seongnam, Korea

- †Corresponding author: Jean Kyung Paik Department of Food and Nutrition, Eulji University, 553 Sanseong-daero, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam 13135, Korea Tel: +82-31-740-7141 Fax: +82-31-740-7370 Email: jkpaik@eulji.ac.kr

© 2025 The Korean Society of Community Nutrition

This is an Open-Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,734 Views

- 48 Download

Abstract

-

Objectives

- This review aimed to elucidate the characteristics of dysphagia and age-related swallowing changes (presbyphagia) in older adults and to comprehensively examine assessment tools and standardized meal management strategies applicable in community settings to propose effective meal management strategies for healthy longevity.

-

Methods

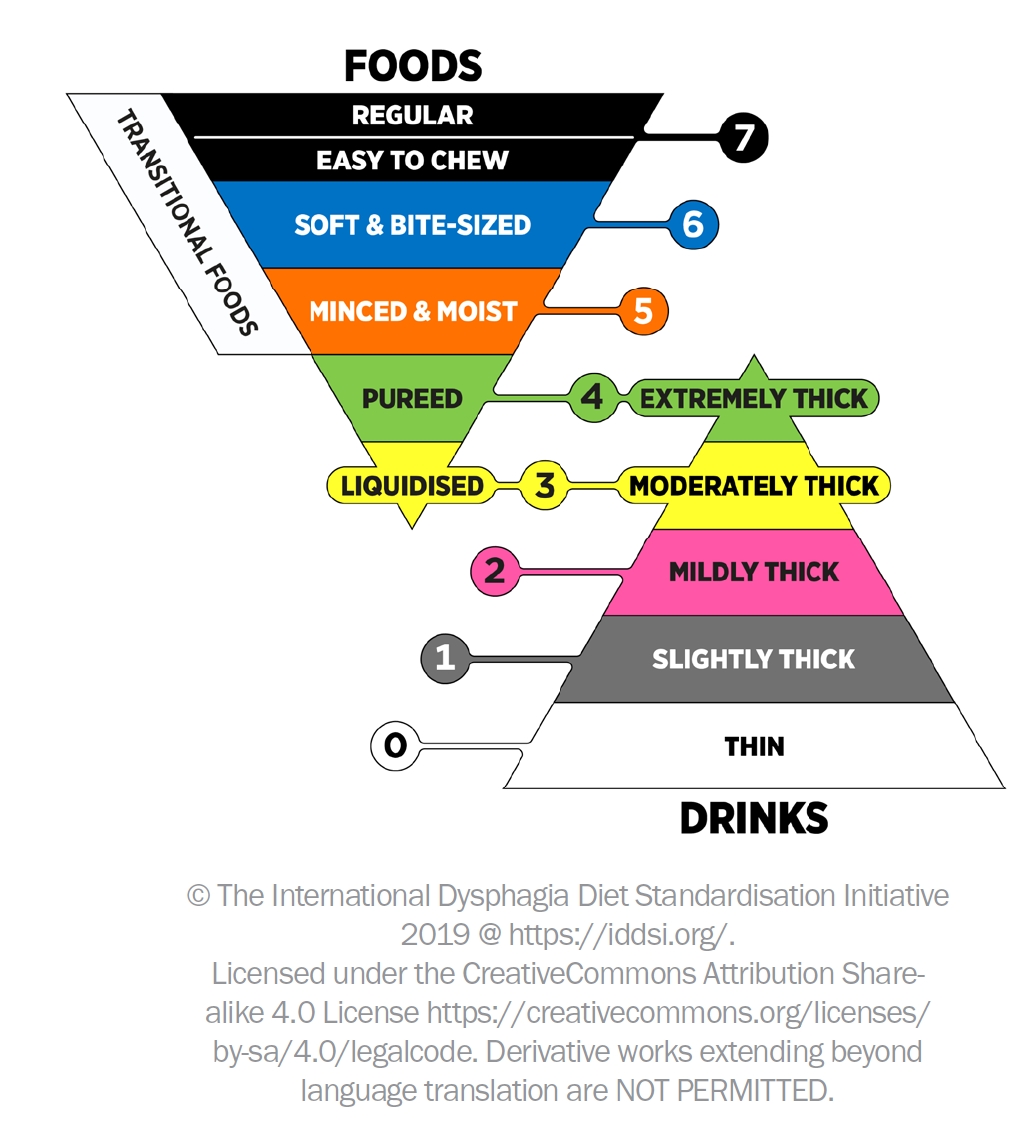

- Domestic and international literatures were analyzed regarding the definition and causes of dysphagia, physiological and structural characteristics and clinical impacts of presbyphagia, assessment and diagnostic tools Korea version of EAT-10 (K-EAT-10) and Korea version of Dysphagia Risk Assessment for the Community-dwelling Elderly (K-DRACE), and the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI).

-

Results

- Dysphagia compromises safe swallowing and nutritional intake in older adults, leading to serious complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, malnutrition, sarcopenia, and reduced quality of life. The K-EAT-10 and K-DRACE proved effective for rapid screening of dysphagia risk in community-dwelling older adults. Moreover, texture-modified meals and viscosity adjustments based on the IDDSI standards are useful for reducing the risk of aspiration and improving nutrient intake. Meals can be classified as liquidized, minced, chopped, or regular, allowing for individualized management.

-

Conclusion

- Presbyphagia is a multidimensional problem, and the integrated use of assessment tools and standardized meals is crucial. Community-based dysphagia management programs and collaboration among dietitians and healthcare professionals are needed to improve the nutritional status and quality of life of older adults.

INTRODUCTION

METHODS

OVERVIEW OF DYSPHAGIA

MECHANISMS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF PRESBYPHAGIA

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS OF DYSPHAGIA

DIETARY MANAGEMENT AND STANDARDIZATION SYSTEMS FOR DYSPHAGIA

CONCLUSIONS

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflicts of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

NOTES

- 1. Lee H, An OH. A study on segmentation of super-aging society considering Korea’s aging characteristics. J Korean Hous Assoc 2025; 36(1): 31-40. Article

- 2. Ministry of Data and Statistics. 2025 Elderly Statistics [Internet]. Statistics Korea; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=10820&tag=&act=view&list_no=438832&ref_bid=

- 3. Kim KR, Hwang NH, Jin HY, Yoo JA. Diversity and sociopolicy response of the elderly in post-aged society. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2020 Dec. Report No. 2020-45.

- 4. Ahn S, Chu SH, Jeong H. Current research trends on prevalence, correlates with cognitive function, and intervention on sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: systematic review. J Korean Gerontol Soc 2016; 36(3): 727-749.

- 5. Kim JI, So HY, Kim HL. Physiological parameters related to health of the elderly. J Korean Public Health Nurs 2020; 14(2): 271-280.

- 6. Kang E, Kim HS, Jeong CW, Kim SJ, Lee SH, Joo BH, et al. 2023 Survey on the status of older adults. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2023 Nov Report No. 2023-84

- 7. Choi HK, Ryu SI, Lee MH, Paik JK. Quality characteristics of baekseolgi added with Pinus koraiensis leaves powder for healthy snacks for the elderly. Culin Sci Hospitality Res 2023; 29(10): 11-18. Article

- 8. The Korean Geriatrics Society. Geriatrics fact sheet 2018 [Internet]. The Korean Geriatrics Society; 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.geriatrics.or.kr/geriatrics/file/factsheet_Kor.pdf

- 9. Korean Classification of Diseases Information Center (KOIOD). 8th Korean Standard Classification of Diseases: digestive system and abdominal symptoms and signs. Dysphagia [Internet]. The Korean Geriatrics Society; n.d. [cited 2025 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.koicd.kr/kcd/kcd.do?degree=08&kcd=R13

- 10. Won JB, Ha JY. The subjective oral health status, dependence of eating behavior and nutritional status of the elderly in nursing facilities according to dysphagi. Asia-Pac J Multimed Serv Converg Art Humanit Sociol 2018; 8(12): 711-720.

- 11. Yang RY, Yang AY, Chen YC, Lee SD, Lee SH, Chen JW. Association between dysphagia and frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2022; 14(9): 1812.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Han Y, Yoon JH. Systematic investigation of dysphagia in Korean community-dwelling older adults. J Speech Lang Hear Disord 2024; 33(1): 189-203. Article

- 13. Dellis S, Papadopoulou S, Krikonis K, Zigras F. Sarcopenic dysphagia. A narrative review. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2018; 3(1): 1-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Bertschi D, Rotondo F, Waskowski J, Venetz P, Pfortmueller CA, Schefold JC. Post-extubation dysphagia in the ICU-a narrative review: epidemiology, mechanisms and clinical management (Update 2025). Crit Care 2025; 29: 244.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Feng HY, Zhang PP, Wang XW. Presbyphagia: dysphagia in the elderly. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(11): 2363-2373. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Lorenz T, Iskandar MM, Baeghbali V, Ngadi MO, Kubow S. 3D food printing applications related to dysphagia: a narrative review. Foods 2022; 11(12): 1789.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Verdú E, Ceballos D, Vilches JJ, Navarro X. Influence of aging on peripheral nerve function and regeneration. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2000; 5(4): 191-208. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Abdel-Aziz M, Azab N, El-Badrawy A. Cervical osteophytosis and spine posture: contribution to swallow disorders and symptoms. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018; 26(6): 375-381. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Siparsky PN, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE Jr. Muscle changes in aging: understanding sarcopenia. Sports Health 2014; 6(1): 36-40. PubMedPMC

- 20. Robbins J, Humpal NS, Banaszynski K, Hind J, Rogus-Pulia N. Age-related differences in pressures generated during isometric presses and swallows by healthy adults. Dysphagia 2016; 31(1): 90-96. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, Rademaker AW, Colangelo LA, Kahrilas PJ, Smith CH. Temporal and biomechanical characteristics of oropharyngeal swallow in younger and older men. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2000; 43(5): 1264-1274. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Ship JA, Pillemer SR, Baum BJ. Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50(3): 535-543. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Shaker R, Li Q, Ren J, Townsend WF, Dodds WJ, Martin BJ, et al. Coordination of deglutition and phases of respiration: effect of aging, tachypnea, bolus volume, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol 1992; 263(5 Pt 1): G750-G755. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Kim SH, Kim JS. Nurse’s knowledge, attitudes and practice of preventive nursing for aspiration pneumonia in elderly. J Korean Gerontol Nurs 2012; 14(2): 99-109.

- 25. Liu T, Zheng J, Du J, He G. Food processing and nutrition strategies for improving the health of elderly people with dysphagia: a review of recent developments. Foods 2024; 13(2): 215.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Kim BR, Son YS, Min KC. Translation and content validity verification of the Korean version of the Dysphagia Risk Assessment for the Community-Dwelling Elderly (K-DRACE). Korean J Occup Ther 2024; 32(4): 39-51. Article

- 27. Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, Pryor JC, Postma GN, Allen J, Leonard RJ. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2008; 117(12): 919-924. ArticlePubMedLink

- 28. Noh DK, Choi SH, Choi CH, Lee K, Kwak SH. Validity & reliability of a Korean-version of Eating Assessment Tool (K-EAT-10): predicting the risk of aspiration in stroke patients. Commun Sci Disord 2022; 27(4): 830-843. ArticlePDF

- 29. Min KC, Kim BR, Son YS. Dysphagia screening and assessment questionnaires for community population: systematic review. Korean J Occup Ther 2024; 32(2): 131-149. Article

- 30. Miura H, Kariyasu M, Yamasaki K, Arai Y. Evaluation of chewing and swallowing disorders among frail community-dwelling elderly individuals. J Oral Rehabil 2007; 34(6): 422-427. ArticlePubMed

- 31. Kim B, Min K, Hong D, Woo H. Standardization of the Korean version of Dysphagia Risk Assessment for the Community-Dwelling Elderly. J Korean Dysphagia Soc 2025; 15(1): 27-36. Article

- 32. The Korean Dietetic Association. Manual of Medical Nutrition Therapy. 4th ed. The Korean Dietetic Association; 2022.

- 33. An S, Lee W, Yoo B. Comparison of national dysphagia diet and international dysphasia diet standardization initiative levels for thickened drinks prepared with a commercial xanthan gum-based thickener used for patients with dysphagia. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2023; 28(1): 83-88. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Jung DS, Choi HY, Park S, Kim JC. A study on the viscosity of senior-friendly foods for quality standards. Resour Sci Res 2023; 5(1): 1-15. ArticleLink

- 35. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Cooking guide for individuals with dysphagia. MFDS; 2019.

- 36. Cha S, Hazelwood RJ, Hong I. Impact of the IDDSI framework on dysphagia risk, nutrition, and personal/environmental factors: a literature review. J Korean Dysphagia Soc 2025; 15(1): 37-54. Article

- 37. International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI). The IDDSI framework (the standard) [Internet]; 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.iddsi.org/standards/framework?utm_source=chatgpt.com

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

| EAT-10 | DRACE | |

|---|---|---|

| Items | 1. My swallowing problem has caused me to lose weight | 1. Do you sometimes have a fever? |

| 2. My swallowing problem interferes with my ability to go out for meals | 2. Do you feel as though having a meal is more time-consuming than before? | |

| 3. Swallowing liquids takes extra effort | 3. Do you sometimes feel as though swallowing is difficult? | |

| 4. Swallowing solids takes extra effort | 4. Do you sometimes feel as though it is difficult to eat something hard? | |

| 5. Swallowing pills takes extra effort | 5. Does food sometimes spill out of your mouth? | |

| 6. Swallowing is painful | 6. Do you sometimes choke during your meals? | |

| 7. The pleasure of eating is affected by my swallowing | 7. Do you sometimes choke when you drink liquid, such as tea? | |

| 8. When I swallow, food sticks in my throat | 8. Are there times when the things you swallowed flow back into your nose? | |

| 9. I cough when I eat | 9. Does your voice sometimes change after eating or drinking? | |

| 10. Swallowing is stressful | 10. Does sputum form in your throat during meals or after eating or drinking? | |

| 11. Do you sometimes feel as though food gets stuck in your chest? | ||

| 12. Are there times when food or a sour fluid flows back from your stomach toward your throat? |

Adapted from Kim Adapted from Noh EAT-10, Eating Assessment Tool-10; DRACE, Dysphagia Risk Assessment for the Community-dwelling Elderly.

KSCN

KSCN

Cite

Cite