Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Korean J Community Nutr > Volume 25(6); 2020 > Article

- Research Article

- Vegetable and Nut Food Groups are Inversely Associated with Hearing Loss- a Cross-sectional Study from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Sunghee Lee, Jae Yeon Lee

-

Korean Journal of Community Nutrition 2020;25(6):512-519.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5720/kjcn.2020.25.6.512

Published online: December 31, 2020

2Researcher, University-Industry Cooperation Foundation, Kangwon National University, Gangwon-do, Korea

-

Corresponding author:

Sunghee Lee,

Email: sunglee@kangwon.ac.kr

- 1,066 Views

- 4 Download

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

Abstract

Objectives

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the associations between food groups and hearing loss.

Methods: Data of 1,312 individuals were used from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013. Hearing loss was determined with a pure tone average (PTA) of greater than 25 dB in either ear. The PTA was measured as the average hearing threshold at speech frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz. The dietary intake was examined with a food frequency questionnaire with 112 food items. The food items were classified into 25 food groups. A weighted logistic regression was used to investigate the association.

Results: Individuals in the highest tertile of vegetables and nuts food groups were less likely to have hearing loss than those in the lowest tertile [Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.58 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 0.38-0.91), P = 0.019; OR = 0.59 (95% CI 0.39-0.90), P = 0.020, respectively], after adjusting for confounding variables of age, sex, body mass index, drinking, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and physical activity.

Conclusions: In this cross-sectional study, we observed that high intake of vegetables and nuts food groups revealed significant inverse associations with hearing loss, after adjusting for confounding variables among 1,312 participants.

Published online Dec 31, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.5720/kjcn.2020.25.6.512

Vegetable and Nut Food Groups are Inversely Associated with Hearing Loss- a Cross-sectional Study from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Abstract

Objectives

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the associations between food groups and hearing loss.

Methods

Data of 1,312 individuals were used from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013. Hearing loss was determined with a pure tone average (PTA) of greater than 25 dB in either ear. The PTA was measured as the average hearing threshold at speech frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz. The dietary intake was examined with a food frequency questionnaire with 112 food items. The food items were classified into 25 food groups. A weighted logistic regression was used to investigate the association.

Results

Individuals in the highest tertile of vegetables and nuts food groups were less likely to have hearing loss than those in the lowest tertile [Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.58 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 0.38–0.91), P = 0.019; OR = 0.59 (95% CI 0.39–0.90), P = 0.020, respectively], after adjusting for confounding variables of age, sex, body mass index, drinking, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and physical activity.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, we observed that high intake of vegetables and nuts food groups revealed significant inverse associations with hearing loss, after adjusting for confounding variables among 1,312 participants.

Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the common health problems among individuals ages 20 to 69 years in 2011 and 2012 with the prevalence rate at 14% [1]. An increase of the elderly population and in the popularity of ear plug devices among young adults indicates a further expected increase in the prevalence rates of hearing loss. In addition, hearing loss affects social relationships with poor communications, causes social isolation and depression [2]. It also may lead to a low quality of daily life [3]. Mechanisms linked to hearing loss have been demonstrated with cochlear damage through oxidative stress and inflammation on auditory nerve cells, reduction of the cochlear blood flow, and sensorineural dysfunction from hair cell loss [4, 5, 6]. Generally, the cochlea is a sensitive organ and is highly susceptible to oxidative stress in the inner ear [7]. Thus, it is important to identify ways to delay hearing loss.

Previous cross-sectional studies on diets that include antioxidants such as vitamins [8, 9] and β-carotene [10] have demonstrated inverse associations with hearing loss. However, previous studies have primarily focused on individual nutrients and dietary patterns. In another crosssectional study, the “Healthy Dietary Pattern”, mainly consisting of fruit, vegetables, and milk, indicated an inverse association with hearing loss [11]. Although dietary patterns were derived from various food groups, individual food group-based associations with hearing loss were not specified. It is important to investigate food group-based associations in order to provide more practical guidelines in terms of specific food choices that could help delay hearing loss.

Therefore, the associations of food group intake with hearing loss need to be investigated to specifically identify which food groups attribute to exacerbating or delaying hearing loss in the general population in order to establish more practical guidelines. Thus, we investigated an association between food groups and hearing loss in a large cross-sectional study of 1,312 participants from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

Materials and Methods

Study population

Data for this study were from the KNHANES conducted in 2013. As a representative sample from a general population, the participants underwent a physical examination, answered questionnaires, and took a dietary assessment during the survey. Approval from the Institutional Review Board (2013-07CON-03-4C) of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was obtained.

Among 4,279 adults ages 19 to 64 years who took a FFQ test in the 2013 KNHANES, those 33 individuals with infeasible ranges of caloric intake such as < 500 or > 5000 kcal per day were excluded. Of 3,706 participants, 1,808 participants were excluded because only adults ≥ 40 years of age were participated in an audiometry test. Among the ones who underwent audiometry, 149 individuals were excluded because of unilateral hearing loss [9] with a > 8 dB pure tone average (PTA) difference between the right and the left ears. Further, 308 participants were excluded due to occupational exposure to noise [9]. Of 1,441 participants, 22 individuals with severe diseases like cancer were excluded because their disease could have affected their diets and 107 adults were excluded due to missing of covariates. The final 1,312 participants were in the final analyses.

Dietary measurement

Using a FFQ, the frequencies of eating 112 food items per week were asked and calculated into serving sizes per day. These items were categorized into 25 food groups based on the nutrient contents [12, 13]. The FFQ has been confirmed with validity and reliability tests [14]. A residual method was utilized as energy adjustment [15].

Audiometric measurement

The PTA was calculated as the average hearing threshold measured at the speech frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in an audiometry examination. Hearing loss was determined if a participant had a PTA of > 25 dB in either right or left ear [11, 16].

Covariates

The variable, physical activity, was defined as walking for > 30 minutes a day and > 5 days a week. Participants who drink alcohol were categorized into three groups including non-drinker, who had not taken any alcoholic drinks for at least a year; moderate drinker, who were neither a non-drinker nor a heavy drinker; and heavy drinker, who drank ≥ 7 drinks of alcohol for men and ≥ 5 drinks for women, ≥ 2 times a week [17, 18]. A participant was determined to be hypertensive based on ≥ 140 mmHg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic blood pressure, or usage of anti-hypertensive medication. Diabetes Mellitus was identified if a participant had a ≥ 126 mg/dL fasting glucose level or used anti-diabetic medication.

Statistical analysis

All of the continuous and the categorical variables were compared between individuals with and without hearing loss to examine the general characteristics of 1,312 using weighted averages and weighted frequencies. The 25 food groups were assessed for the tertile ranges based on their consumption values. According to the tertile ranges, the characteristics of the participants were analyzed with chisquare and regression tests. To investigate the associations between each of the food groups and hearing loss, a logistic regression model using survey procedure with integrated weights was used for multi-stage sampling. Adjustments for potential confounding variables were considered with age, sex, energy, physical inactivity, drinking, smoking, diabetes, body mass index (BMI), and hypertension. Age, sex, smoking variables were included based on the significant differences between those with hearing loss and without as shown in the Table 1. Other variables such as BMI, physical activity, and drinking were considered according to previously demonstrated associations [19, 20, 21]. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). The P-value being less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Table 1

General characteristics (n=1,312)

Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of all the 1,312 participants. The average age was 50.53 years. The average age of participants with hearing loss was significantly higher than those without hearing loss (55.60 vs. 49.56, P < 0.001). Participants with hearing loss were likely to be men than women (58.46 vs. 40.75, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the proportion of current smokers was greater in those with hearing loss than in those without (P < 0.001). However, no differences between participants with and without hearing loss in BMI, energy intake, physical activity, and alcohol drinking were found. Additionally, the prevalence rates of hypertension and diabetes were different between those with and without hearing loss.

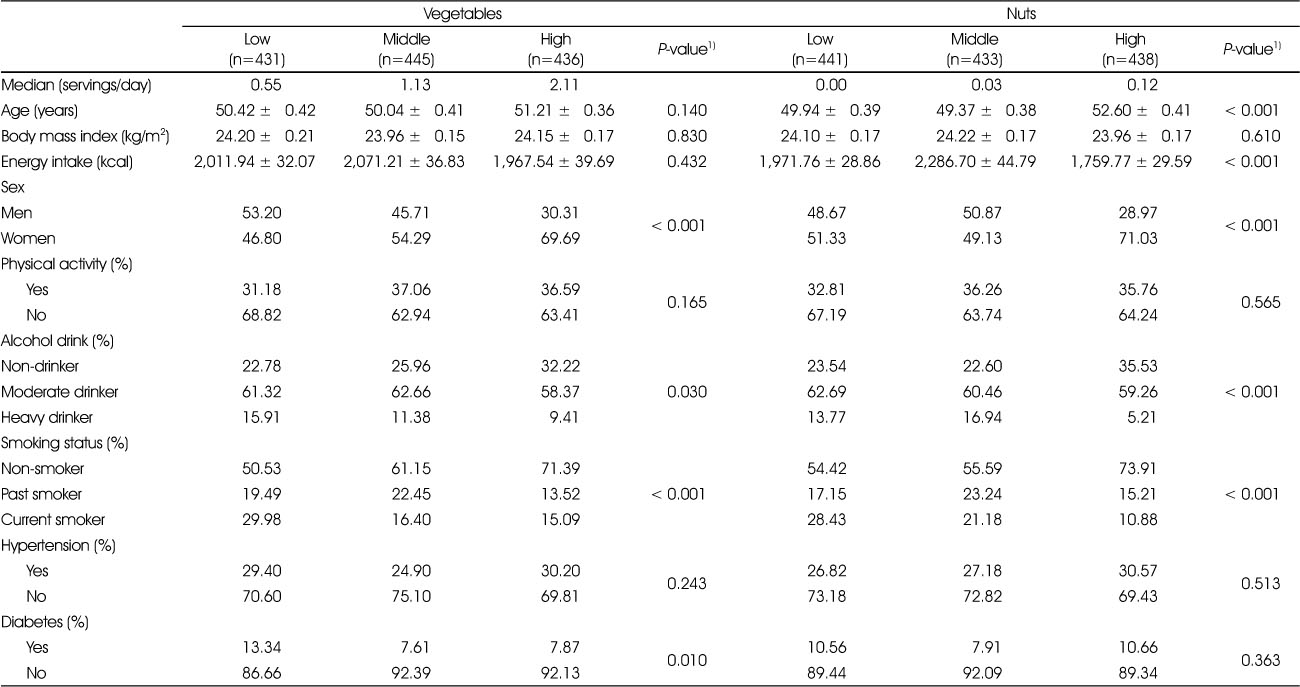

Table 2 shows the characteristics according to the tertile ranges of the two food groups of vegetables and nuts. Participants in the groups of higher vegetable intake were more likely to be women (46.80%, 54.29%, 69.69%: P < 0.001), less likely to consume alcohol (15.91%, 11.38%, 9.41%: P = 0.030), less likely to smoke (29.98%, 16.40%, 15.09%: P < 0.001). Individuals in the group of higher intake of nuts were likely to be older (P < 0.001), less likely to have total energy intake (P < 0.001), likely to be women (P < 0.001), less likely to have alcohol consumption (P = 0.030), and less likely to currently smoke (P < 0.001).

Table 2

Characteristics of the study participants according to vegetables and nuts food groups (n=1,312)

Table 3 shows the associations between the various food groups and hearing loss among 1,312 participants from the general population. As compared with participants in the lowest tertile, those participants in the highest tertile of vegetables and nuts food groups were less likely to have hearing loss (P for trend = 0.019 and 0.020, respectively).

Table 3

Associations between food groups and hearing loss (n=1,312)

Discussion

We found significant inverse associations between intakes of vegetables and nuts food groups and hearing loss among 1,312 participants aged between 40 to 64 years from a general population, after adjusting for confounding variables of age, total energy intake, sex, drinking, BMI, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and physical activity. This study was unique in that it reported food group-based associations with hearing loss, suggesting a more practical dietary guidelines with specific food choices that could help delay hearing loss.

Our findings of significant inverse associations between vegetables and nuts food groups with hearing loss are concurrent with previous cross-sectional studies that suggested antioxidants in foods to delay hearing loss by preventing sensorineural impairment in the cochlea [8, 9, 10]. A prospective cohort showed a positive association with high sugar foods on age-related hearing loss [22]. In addition to studies with a nutrient focused approach, a previous study with dietary patterns presented a significant inverse association of hearing loss with a Healthy Dietary Pattern that was mainly featured with food groups of cereals, fruit, bread, vegetables, and milk [11]. As noted in our study, the vegetable food group, a part of the Healthy Dietary Pattern, indicated a significant inverse association on hearing loss [11]. Vegetables are known to provide vitamins, minerals, and fibers. These nutrients of vitamin A [8], vitamin C [10], folate [9] and vitamin E [8] have been demonstrated to have inverse associations with hearing loss. Folate deficiency has been reported to cause damage to the neurons and the vessels of the auditory system [9, 23, 24]. Vitamin B12 deficiency has also been shown to increase homocysteine level which promotes free radical formation and exerts a thrombogenic effect on the blood flow in the cochlea [25]. Additionally, other nutrients like riboflavin, retinol, and niacin have an inverse correlation with hearing loss in older adults [26].

Our findings also demonstrated an inverse association between nuts food group and hearing loss. Nuts, such as peanuts and chestnuts, are known to contain monounsaturated fatty acids like oleic acid [27], selenium, zinc, and vitamin E, which are demonstrated to be antioxidants [28], that protect the auditory nerves [29], have beneficial effects on the blood vessels in the cochlea [30], and help reduce inflammation [31].

The underlying mechanisms of the association linked to the food groups and hearing loss have not been fully elucidated. Our current findings align with previous suggestions of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents in the vegetables and nut food groups contributing to decreasing the risk of hearing loss. One of possible mechanisms of exacerbating hearing loss is that reactive oxygen species in the inner ear induce neuronal cell impairment and affect t he c ochlear b lood f low [32, 33]. Vitamins from vegetables have been demonstrated to act as antioxidants, removing singlet oxygen [10, 34]. Monounsaturated fatty acids and minerals from nuts food group have also been shown to reduce inflammatory markers [35]. The vegetables and nuts food groups decrease oxidative stress and also reduce proinflammatory markers.

Although participants in the middle tertile showed a reduced likelihood of having hearing loss in the seaweed and fruit food groups, neither the seaweed nor fruit food groups showed the statistical significance of a quadratic term for hearing loss (P = 0.08 and 0.05, respectively). Additionally, multi-collinearity among independent variables as well as the correlation between vegetables and nuts food groups were examined and no collinearity was confirmed. Also, sex-specific difference was examined but confirmed not to be statistically significant. It was examined if BMI played a role as a mediator due to the suggested oxidative stress. Then, the test results confirmed that the BMI variable was not a mediator, but rather considered as a confounding factor.

Our study has its strengths and limitations that are taken into considerations when interpreting our findings. First, as our study population was a large and nationally representative sample from the general population, it gives enough statistical power to demonstrate significance and retains the capability to generalize our findings into other populations. Second, the food group-based approach of our current study contributes to establishing a practical guide geared toward delaying hearing loss. However, this study also has limitations. The study design was a cross-sectional study, which imposed a limit on examining causality. Furthermore, socioeconomic variables such as education or income were not included as part of the confounding variables, which may have affected the results.

In conclusion, we found that vegetables and nuts food groups had significant inverse associations with hearing loss among the 1,312 participants from a general population, after adjusting for confounding variables.

References

-

Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontol 2003;43(5):661–668.

-

-

Puga AM, Pajares MA, Varela-Moreiras G, Partearroyo T. Interplay between nutrition and hearing loss: State of art. Nutrients 2019;11(1):35.

-

-

Moller AR. In: Hearing: Anatomy, physiology, and disorders of the auditory system. San Diego: CA Plural Publishing; 2012.

-

-

Willett W. Implications of total energy intake for epidemiological analyses. In: Willett W, editor. Nutritional epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 273-301.

-

-

Lee SY, Jung G, Jang MJ, Suh MW, Lee JH, Oh SH. Association of chocolate consumption with hearing loss and tinnitus in middle-aged people based on the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2012-2013. Nutrients 2019;11(4):746

-

-

Tak YJ, Lee JG, Yi YH, Kim YJ, Lee S, Cho BM. Association of handgrip strength with dietary intake in the Korean population: Findings based on the seventh Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES vii-1),2016. Nutrients 2018;10(9):1180

-

-

Sardone R, Lampignano L, Guerra V, Zupo R, Donghia R, Castellana F. Relationship between inflammatory food consumption and age-related hearing loss in a prospective observational cohort: Results from the salus in apulia study. Nutrients 2020;12(2):426

-

-

Kim TS, Chung JW. Associations of dietary riboflavin, niacin, and retinol with age-related hearing loss: An analysis of Korean national health and nutrition examination survey data. Nutrients 2019;11(4):896

-

-

Sabaté J, Oda K, Ros E. Nut consumption and blood lipid levels: A pooled analysis of 25 intervention trials. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(9):821–827.

-

- Related articles

-

- Prevalence of coronary artery disease according to lifestyle characteristics, nutrient intake level, and comorbidities among Koreans aged 40 years and older: a cross-sectional study using data from the 7th (2016–2018) Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Ultra-processed food intake and dietary behaviors in Korean adolescents: a cross-sectional study based on the 2019–2023 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Self-reported weight change and diet quality in relation to metabolic syndrome among Korean cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2019–2021

- The dietary factors associated with sleep duration in postmenopausal middle-aged women: a cross-sectional study using 2019–2023 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data

- Analysis of the relationship between sugar intake and cancer prevalence: a cross-sectional study using the 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Trends in growth and nutritional status of Korean toddlers and preschoolers: a cross-sectional study using 2010–2021 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data

KSCN

KSCN

Cite

Cite